It's hard to think about heating oil in the midst of the hottest 21-day period in Boston's recorded history. But while gas prices started dipping downward the past month, the…

In data: Here’s how heat pumps can cut carbon and save the world

We installed a mini-split heat pump in our home in 2021 — not a whole-home system, just one wall-mounted unit in the living area, because that was all we could afford at the time. (The rebates are much, much better now — you can get $10,000 back from MassSave, plus up to $2,000 in federal tax credits.) And now that we’ve used our heat pumps for a couple of winters, I decided to analyze our heating history to see what kind of carbon impact they’re having, using 10 years of real-world data from our home.

Long story short? Simply supplementing our gas boiler with a mini-split heat pump has cut our carbon emissions by almost 4 tons a year — more than if we took our car off the road entirely.

| I wrote a book! It’s called ‘Home Buying 101: Your Essential Guide to Buying Your First Home‘ and you can get it from Amazon, Bookshop.org, Barnes & Noble, or your local bookstore. |  |

How heat pumps (and insulation) cut carbon emissions

While our heat pump is really just a supplemental heat source — we have one wall-mounted mini-split head in the main living area, not one in each bedroom and the kitchen as you’d want for a complete conversion — we used it almost exclusively last winter, only turning on our gas boiler on the very coldest single-digit days for a little boost. (It’s been glorious in the summer, too, quietly replacing three noisy, inefficient window air conditioners.)

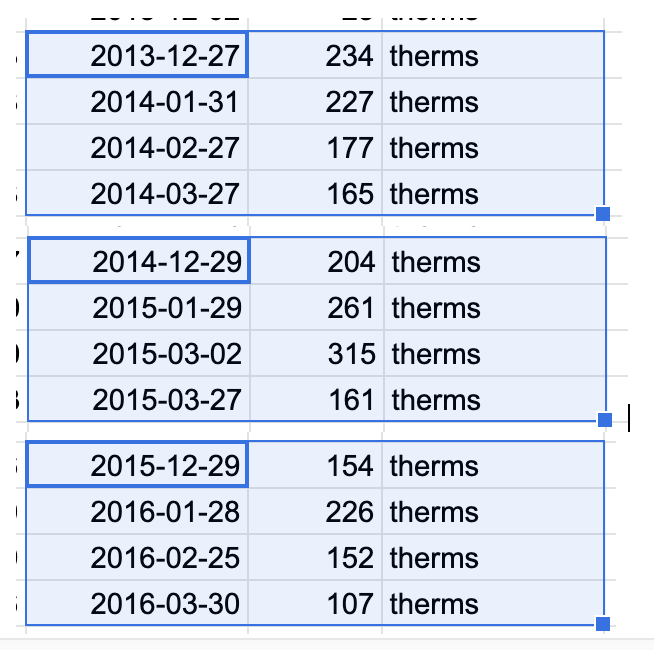

I recently pulled our usage history from National Grid, just out of curiosity. And it goes back 10 years, to when we had oil heat, providing a good baseline for our average winter gas usage minus heating: Before we converted our boiler from oil to gas, we used about 24 therms a month in winter for hot water and cooking.

In 2013, we got a new natural gas boiler installed. For the next five years, we averaged about 190 therms per month in winter (December through March). The most we ever used was during the snowpocalypse that was Feb. 2015.

Then, in 2018, we got insulation blown into the walls, mostly paid for by MassSave. I can’t say the contractors did a great job — their sloppy work sent my immuno-compromised wife to the hospital, in fact — but the added insulation did cut our gas use substantially in the winters that followed.

In the three winters after getting insulation blown in, we averaged 143 therms per month from December through March, compared to 190 therms per month beforehand — about 25% less:

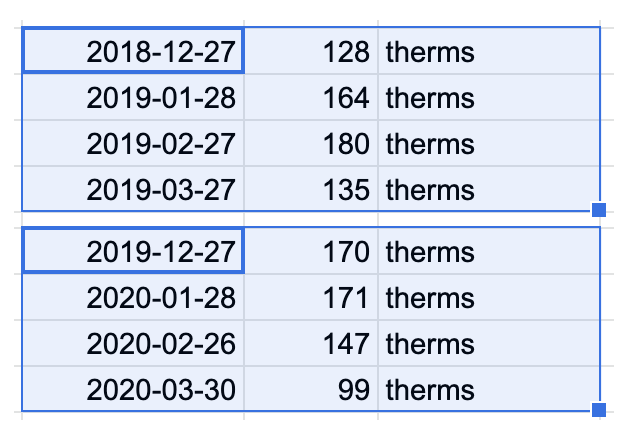

In fall 2021, we got our mini-split heat pump installed. Again, not a whole-home system, just a single wall unit. But our home is all on one floor (a typical two-decker) so the air circulates; if it’s 70F in the living room, the bedrooms are about 65F to 67F, good sleeping temps.

So we used our mini-split almost exclusively the last two winters, only using the gas heat on a few truly frigid days. (I need to emphasize, this is not because the heat pump didn’t work in ultra-cold temps — it did, like a champ! It’s just because we don’t have a true whole-home system. So our living room would still be nice and warm, but the extremities — the bedrooms, bath, stairway, etc. — were getting too chilly with only one wall unit in the living room.)

And our gas usage that first winter? It never topped 37 therms in a month, averaging about 32 therms from December through March. Our electric bill went up, obviously — but not by as much as our winter gas bills used to be. The following winter (2022-23), we averaged 36 therms a month — peaking at 52 therms in a single month when low temps plunged to a record –10F in early February.

Now for some carbon math. Burning a therm’s worth of natural gas produces 11.7 pounds of carbon dioxide. After getting insulation blown in, we used about 47 therms less gas per month, cutting more than 2,000 pounds — over a ton — of carbon dioxide emissions each winter.

Using our heat pump the last two winters (powered by 100% renewable electricity, through our rooftop solar panels and the Green Energy Consumers Alliance) we cut our average winter gas usage from 190 therms (pre-insulation) to an average of 34 therms per month. So from December through March, we cut our carbon emissions by a total of roughly 7,300 pounds — nearly FOUR TONS a year.

For context: Burning a gallon of gasoline releases about 20 lbs of carbon into the atmosphere. At 10,000 miles a year, and 30 miles per gallon, we use an estimated 333 gallons of gas per year driving our Subaru Impreza. That’s 6,700 pounds of carbon dioxide.

So switching to an electric heat pump essentially had as big of a carbon impact as taking our car off the road entirely, or replacing our gas vehicle with an EV. (Which we intend to do with our next car — but for now, that’s a big win!)

If you don’t use solar power, or haven’t signed up for renewable energy from your electricity provider (National Grid allows you to choose 100% renewables in your electric service, for example), then the carbon impact won’t be quite as dramatic — but it will still be a big improvement, since 59% of the electric grid in Massachusetts is carbon-free as of 2023, and that number is required to increase by law.

The main point is: CO2 is a gas that floats around in the air — so think about how much four TONS of that would be. I mean, thousands of pounds of air. Like, that’s a LOT of carbon dioxide! And this is the impact of just one family, in one relatively small (1,150 sq. ft.) home, making a very simple switch — and not even using a whole-home heat pump system.

Scale that up to a million households, or 10 million, or 100 million, and you can see why switching from oil or gas to electric heat pumps could help save the world — if we get going fast.